UPSIDE COMPARISON:

HUB WEST BALTIMORE vs PORT COVINGTON

“With its low economic baselines, high poverty costs and unparalleled access to Washington’s powerful economic engine, HUB West Baltimore could rapidly eclipse even Port Covington (and its $650 million city taxpayer subsidy), in becoming a leading source of growth to city and state coffers - both from revenue increases and cost savings.”

A Tale of Development in Two Key Parts of the City

Perhaps the city’s most visible - and certainly it’s most expensive - current development, is a neighborhood scale waterfront project, known as Port Covington. Located on a peninsula jutting out into the Patapsco River, the area is adjacent to I-95 as well as the popular neighborhoods of Locust Point and Federal Hill. The development was the brainchild of billionaire Under-Armour founder Kevin Plank. Dangling the prospect of a new headquarters for his then-fast-growing company, Plank and his development team were able to secure massive subsidies from the city in the form of a $660 million tax-increment financing (or TIF) package.

Leaving aside the many questions (detailed in part below) about those subsidies and the project overall - even if it succeeds as originally proposed, the Port Covington subsidy package raises all the age-old questions in Baltimore about who gets subsidies, why they get them and where they live. The case of Port Covington’s outsized TIF package (by far the city’s largest ever), versus the conspicuous lack of subsidies for the critical HUB West Baltimore Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) area - despite there being arguably a bigger economic upside in the latter (one potentially achieved with a fraction of the investment) - seems to raise red flags.

The questionable case of Port Covington by itself is explored further on in this section. But first, here’s a quick comparison of some very basic numbers that set these two project focus areas apart:

Sources:

1 - Port Covington subsidy detailed further below in text. HUB West Baltimore subsidy describes the estimated cost of a new multi-modal West Baltimore MARC station - the only additive infrastructure cost outlay requested for the specific three clusters of neighborhoods adjacent to the West Baltimore MARC Station: “Sandtown-Winchester Harlem Park”, “Greater Rosemont”, and “Southwest Baltimore”.

2 - Port Covington upside projection is described in an MOU with the city (shown below). HUB West Baltimore upside is a projection of just partial savings from only 3 significant projected cost reductions, also described in a table below. Potential increases in tax revenue - which could be substantial - are not even factored into this HUB West Baltimore “upside” number.

3 - Source for Port Covington: https://www.southbmore.com/2020/06/23/port-covington-updates-for-chapter-1b-affordable-housing-totals-hotel-added/. HUB West Baltimore total represents goals for additional affordable housing creation utilizing HB1239, the Cardin Neighborhood Homes Investment Act, the Affordable Housing Trust Funds and other sources of funds, to convert 1/3 of the current vacant properties in the three neighborhood clusters, into affordable housing owner-occupier units in the next 15 years. This would be in addition to a projected retention of existing residents of >40% (and as much as 50%), regardless of the amount of revitalization ultimately occurring there.

4 - BNIA Vital Signs, US Census. https://bniajfi.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/VitalSigns14_Census.pdf, https://vital-signs-bniajfi.hub.arcgis.com/apps/vital-signs-19-census-demographics/explore and https://health.baltimorecity.gov/sites/default/files/NHP%202017%20-%2048%20South%20Baltimore%20(rev%206-9-17).pdf. Note “South Baltimore” is a both a census designation and a Baltimore City Dept. of Planning designation that encompasses the neighborhoods of Locust Point and Riverside, in addition to Port Covington.

5 - Ibid BNIA, US Census: https://bniajfi.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/VitalSigns14_Census.pdf

Revenue and Savings Projections Compared

“The upside for city and state budgets at the HUB West Baltimore site is likely greater than the potential from Port Covington, achievable in a shorter amount of time, and would require $1 billion dollars less in subsidy. ”

The Port Covington project developers offered their “best case” scenario for direct contributions to city and state coffers at full build out, 20-25 years from now (assuming the project makes it to that point). They laid out the projections specifically in an MOU with the city:

Meanwhile, across the city at HUB West Baltimore, in just the three neighborhood clusters around the West Baltimore MARC Station (Sandtown-Winchester Harlem Park, Greater Rosemont, Southwest Baltimore), the very real possibility exists that, even in a modest revitalization scenario, city and state budgets could see equal or even greater reductions in costs than the expected added revenues from Port Covington. How?

We believe it’s reasonable to assume that the three costs shown in the chart below are at least, in part, poverty related and/or correlated. So any increased diversification of incomes in the three neighborhood clusters should also bring about a reduction in these costs - and likely much sooner than Port Covington’s expected full build-out. Reductions in these costs by half aren’t out of the question in 15 years, or even a decade.

And because these cost numbers are so high, and income levels are so low (on average), progress could be dramatic. But also, it’s important to note that none of these cost reductions would happen in a vacuum, so there would be significant increases in tax revenue from these areas occurring concurrently, further padding city and state budgets.

In short, the upside in HUB West Baltimore is probably greater than that of Port Covington, and could be realized more quickly, and with practically no subsidies - just smart, targeted government leadership.

The Population Lens

Another way of looking at the question of where development subsidies should go is to look at the question of where it is - and is not - needed.

According to the latest census department data, the South Baltimore census tract (where Port Covington is located), was already gaining population in the last decade, and not in a little way - up nearly 30% in 10 years! Whereas, the neighborhoods around HUB West Baltimore were hemorrhaging it - down 20-30% in that same time.

So the big question is: why did the largest TIF subsidy in city history go to a project in an area that was already growing at 30%? With that kind of population growth occurring - particularly in the context of a city that was shrinking in that time - Port Covington could have reasonably been considered as potentially the next hot city neighborhood - regardless of whether subsidies were used there or not.

On what economists and real estate report-writers call the “But For” test - but for the subsidy, development wouldn’t have happened - these growth numbers suggest that Port Covington fails, because development was already rushing right up to Port Covington’s door.

“The big question is: why did the largest TIF subsidy in Baltimore City history go to a project in an area that was already growing at 30%?”

The Development Momentum Lens

Pictures are worth a thousand words. Below are October 2021 views of and from Wells Street in South Baltimore, directly adjacent to the northern border of the Port Covington development area. All of these buildings were completed or planned long before any development at Port Covington was finalized. In short, the area was already booming with luxury condos, perhaps as much, or more, than any other area in Baltimore. So why was a subsidy - in a waterfront area, for a development largely benefitting one of the richest men in Maryland - necessary when development on Port Covington was clearly already going to happen?

“The South Baltimore area was already booming with luxury condos, perhaps as much, or more, than any other neighborhood cluster in the city.”

Unneeded Subsidy? - Wells Street in South Baltimore is effectively directly adjacent to the Port Covington project. All of these buildings - many of them luxury condos - were already completed or planned before the Port Covington project was finalized.

The View from Wells Street - here you see just how close the Port Covington project is to this already-booming area. it’s just steps away underneath I-95.

Port Covington in Detail

In 2012, Plank-connected entities began, spending more than $100 million quietly acquiring land on the Port Covington peninsula. And then with the stated objective of developing the area as a residential and office mixed-use neighborhood, his team began to pursue public subsidies.

They sought $1.1 billion in subsidies from local, state and federal governments, in part to pay for major infrastructure projects, but also, it turns out, to pay for $33 million in reimbursements (p.274) - for things such as “soft costs”, which include engineering, architecture, city permitting and lobbying fees (p.275), among others. Federal lobbying costs alone, from one DC-based lobbyist, reportedly cost nearly $400,000 - reimbursed by the taxpayer-provided TIF. And meanwhile, one source reported that the development team gave over $80,000 to key state and local elected leaders in the lead-up to the crucial approval votes.

“Federal lobbying costs alone, from just one DC-based lobbyist, reportedly cost nearly $400,000 - reimbursed by the taxpayer-provided TIF.”

In the Fall of 2016, a Baltimore City bill (16-0670) authorizing up to $660 million in debt issuance to support the project was approved by the City Council and signed into law by Mayor Young. The first "tranche”, or part, of that debt - $137,485,000 - was issued. By 2050, the city will have paid approximately $251,925,000 in debt service on those bonds alone. The hope is that the increase in tax revenue from development will cover those costs, as well that of the additional tranches.

The bonds were ultimately issued by a State of Maryland entity because Baltimore City finance leaders were worried about the city maxing out their ability to issue bonds. Steve Kraus, the city’s deputy finance director at the time, to the Baltimore Sun: "Any TIF of this size we're going to have to use a conduit issuer. We just can't take on this kind of a liability at this time."

Plank-controlled companies were originally expected to be the initial buyer in each bond sale, making the bonds cheaper to issue to the city, according to the Baltimore Sun. But that never materialized.

The developers told lawmakers and the public that the central driver of success was going to be the construction of a 50-acre, 3.9 million square foot Under Armour campus at Port Covington, which would eventually host more than 10,000 employees and potentially seed and stimulate the creation of another 10,000 jobs.

But since then, the company has experienced declining sales, accounting questions and multiple corporate restructures. Plank is no longer the CEO (although he remains chairman and “brand chief”). And the new headquarters has been dramatically scaled-down, with the timetable for construction and a move uncertain.

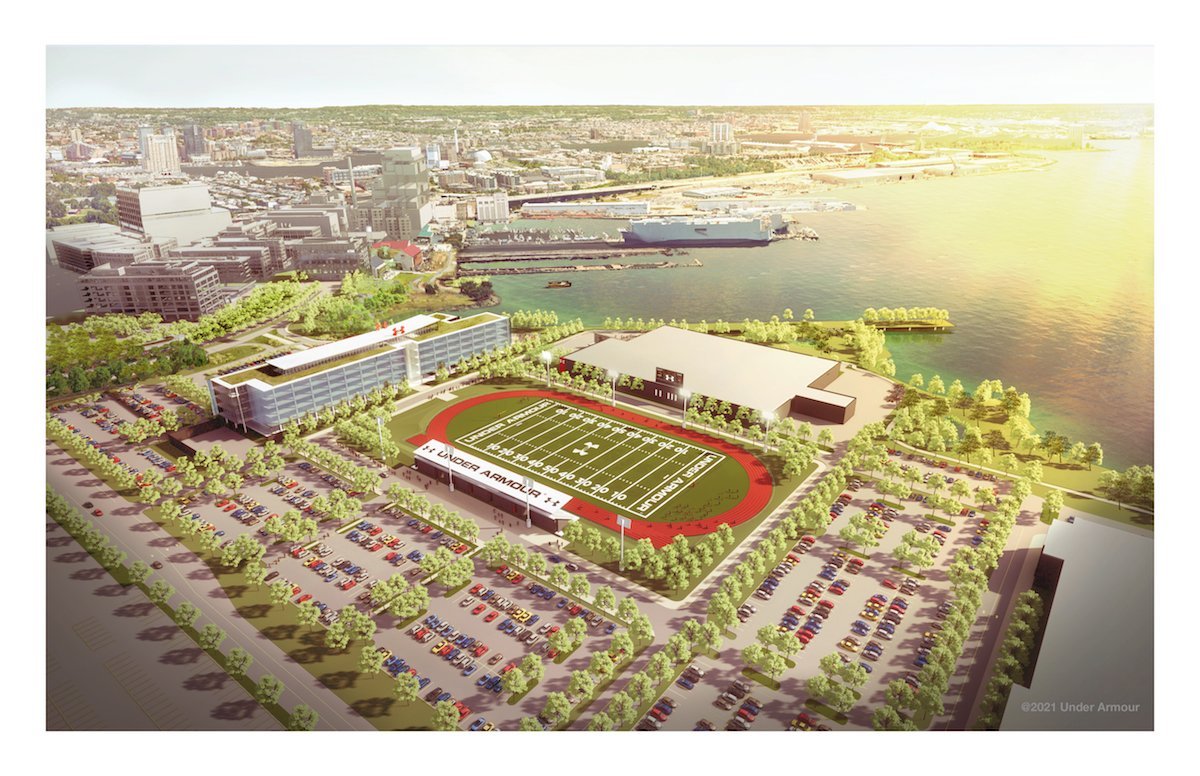

That Was Then - Under Armour’s original headquarters plan, as sold to the public:

This is now - Latest (2021) scaled-down plan for Under Armour’s Port Covington HQ:

Meanwhile, regarding new construction - In this latest 2021 plan, the only new building constructed for this “headquarters” will be the one glass-fronted structure adjacent to the playing field. The two circled buildings (below in red) are already-existing structures currently occupied by Under Armour, and the rest of the land is now slated to be parking lots.

Also note: all the structures on the middle right of the below image are existing as well and not part of the redevelopment project.Further Reading

Read about how a scaled-back Under Armour HQ may have saved the Port Covington project

See how property tax payments from the project will not cover bond payments for the first 11 years

Read about how the ACLU asked Mayor Young to postpone the subsidy vote - here and here

Read about how Plank’s development team said they’d pay for planning and design, whereas it looks like those costs were covered by TIF reimbursements

See how one analysis projects the developer’s rate of return to be 11.4%

Read how the scale-down of the Under Armour HQ has politicians seeking to reevaluate the project

See how what started as “Cyber Town USA” is now being marketed as a biotech hub

Read how Kevin Plank teamed with Goldman Sachs to be the primary investors - and primary beneficiaries of TIF infrastructure improvements.

See here how a highly questionable and seemingly erroneous designation as a federal “Opportunity Zone” also made them windfall beneficiaries of huge tax breaks, even though these breaks were designed to spur development in poor areas, and the poverty rate in South Baltimore is the 2nd lowest in the city. Also more here

Read how the president of BDC now says the TIF package was never contingent on Under Armour moving its headquarters to Port Covington

Read how as of March 2022, Port Covington still appears to have no major tenant leases signed.

Read more…

…about how skewed investment and subsidies has always been a part of Baltimore’s government: