INTRODUCTION

What’s Happening Now?

Rapid, equitable, transformational revitalization in the neighborhoods directly adjacent to the West Baltimore MARC Station.

HUB West Baltimore Community Development Corporation (HWB) is currently guiding developers large and small to the area, and working with the city, state and federal government to catalyze large-scale transit-oriented development (TOD) in the immediate blocks around the station. In addition, HWB is taking a lead role in community planning for the future conversion of the Route 40 “Highway to Nowhere” into a national showpiece of adaptive-reuse of a misguided “urban renewal” project. And finally HWB is working hard in the key areas of creation and preservation of affordable housing in the focus zone, as well as in the implementation of critical quality-of-life initiatives.

What’s the Focus Area?

The focus of HUB West Baltimore Community Development Corporation is the area enclosed by the 6-10 block radius around the West Baltimore MARC Station, described in the map below. The borders of the focus area of HWB CDC are W. Lafayette Street to the north, Monroe Street to the east, Frederick Avenue to the south, and Franklintown Road to the west.

The focus area includes roughly 80 blocks that currently represent arguably the most disinvested area of the entire State of Maryland. But owing to the low baseline of economic activity and the unique transportation service upgrades coming to the MARC station, those blocks also describe perhaps the greatest opportunity for year-over-year growth in economic output, development, and real estate appreciation in the entire region.

The HUB West Baltimore Tentpoles:

Economic Development

Affordable Housing Creation and Preservation

Transportation

What Are the Most Critical Immediate Catalysts Needed?

1. Pilot MARC Express Service

A seamless connecter to the downtown DC job market. Even a limited pilot service of just two express trains southbound in the morning, and two northbound in the afternoon would be transformational to the HUB West Baltimore neighborhoods.

The value proposition - both for Baltimoreans wanting to live closer to jobs in Washington, and Washingtonians relocating to Baltimore for cheaper housing - is as compelling as its ever been in Baltimore.

Currently, MARC is running only one express train from Washington, and it drives right by the West Baltimore station at exactly 30 minutes from Union Station, BUT DOESN’T STOP. That can’t continue - those trains are too important to HUB West Baltimore revitalization, and HUB West Baltimore is too important to the larger Baltimore - and State of Maryland - economies.

2. Neighborhood Homes Investment Act (NHIA)

Along with an analogous state bill that passed in 2021 (Maryland bill HB1239/SB0859 - thank you Delegate Lierman and Senator Hayes!), the NHIA is potentially the greatest game-changer for the vacant property problem in decades, and similarly would be THE key weapon in the fight to create affordable housing OWNERSHIP in West Baltimore. The NHIA is a federal bill, co-introduced by Maryland Senator Cardin, that gives individuals and developers a 35% subsidy of development costs (including acquisition, demolition and construction), if and only if, those properties are sold as affordable housing. So low-income families are instantly turned into homeowners with sustainable mortgages that can begin to participate in this country’s greatest creator of family wealth - the housing market.

As of the end of November 2021, the NHIA was still part of the Build Back Better reconciliation bill being debated in the US Senate. And Senator Cardin’s staff have assured HUB West Baltimore that he is going to fight hard for its inclusion in the final version. If renovating vacant properties (and selling them as affordable housing - as is required by the legislation) were to become profitable, then that alone may be a game-changer for West Baltimore, and for its long-marginalized communities and families.

3. A New Modern, Multi-Modal, Centerpiece West Baltimore MARC Station

The future “Transit-Oriented Development” (or TOD) center of the HUB West Baltimore neighborhoods. The incremental cost of building a more substantial new MARC station than the simple platform renovation that is currently planned as part of the Douglass/B&P Tunnel project, would be approximately $15-20 million. Construction is years away, but planning is happening now, and West Baltimore needs a seat at that planning table to emphasize how important it is for Amtrak, MARC and their designers to thing big, think multi-modal, and think critical centerpiece structure, not just for MARC, but for the entirety of West Baltimore, and the economic future of the city overall.

A marquis, higher capacity, showpiece station would anchor and help spark development of a new TOD center in that location, which would represent an entirely new way of thinking about West Baltimore’s relationship to Washington - as a gateway to that powerful economic center. But it would also be nothing short of a keystone development for West Baltimore itself - finally, truly and completely knitting together, with its commercial center and network of pedestrian bridges, the neighborhoods north and south of Route 40.

Coupled with a reimagined “Highway to Nowhere”-turned-Franklin Dell bookending the eastern edge of the TOD district, and a restarted Red Line project, the station and TOD center, and the neighborhoods around them, would be Baltimore’s next great revitalization success story - and critically, they wouldn’t be anywhere near the waterfront.

The Economic Effect: $250 Million Annually (in increased city and state tax coffers in just a decade)

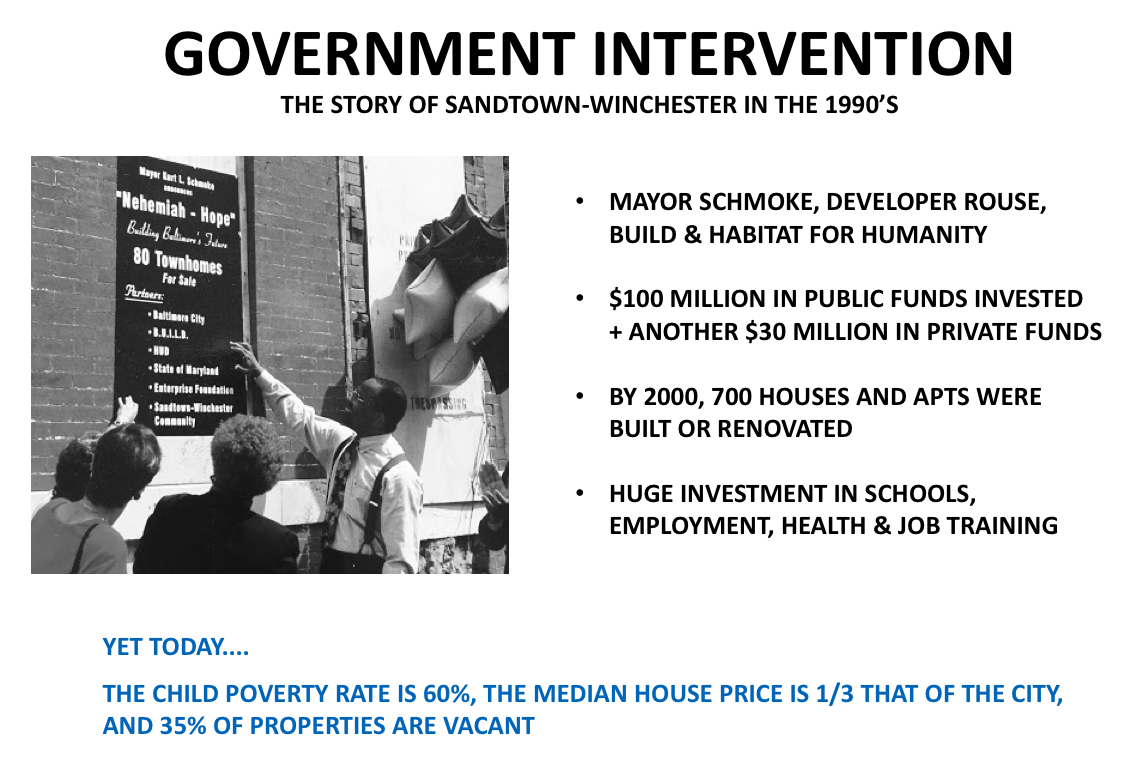

Transformation - plain and simple. The economic baselines are so low in West Baltimore we could easily be talking about 100% growth in a decade, or even half a decade. In concert with the Baltimore-Washington Transportation Research Group, we did several economic studies examining what that growth could reasonably look like in the wider three neighborhood clusters around the West Baltimore MARC Station, what the study called the Key Focus Area, or KFA (Sandtown-Winchester Harlem Park, Greater Rosemont and Southwest Baltimore). We looked at what would be the primary manifestations of that growth. For the sake of simplicity, we settled on just three statistics to focus on for growth and savings potential (see below). These costs are at least partly rooted in poverty we believe, and therefore would be decreased significantly by a shift toward greater economic diversity.

Dramatic movement in these costs would be reasonably expected to occur in even just a moderate revitalization scenario. And those incremental movements could translate into hundreds of millions of dollars annually in increased revenue and savings for city and state budgets - as much or even more than the contribution to city and state tax coffers projected, for instance, at the Port Covington site that is subsidized with $1.1 billion in federal, state and city taxpayer assistance. That controversial, and now scaled-back Port Covington development isn’t expected to be at “full development” for another two decades from now (if ever), whereas HUB West Baltimore could be revitalized and humming within a decade, according to our projections.

Here’s an example of just one of those increased revenue streams - real estate taxes - and how a modest revitalization scenario could quickly turn into real transformational dollars for city and state governments:

But what’s going to drive those increases in property values beyond just better access to Washington from Baltimore and vice-versa? The historic differential in house prices between the two cities, as well as the need for future affordable housing in the region near high-capacity transit.

In short, revitalization in West Baltimore could quickly become an economic driver not just for the city, but for the state overall - in much the same way that Brooklyn, NY went from large-scale disinvestment in the 1990s to a tax-generating machine, when it discovered the value that lies in its proximity to Manhattan. Such a transformation could easily happen here in West Baltimore, the time for it is now, and it could be realized with just the relatively tiniest of taxpayer outlays.

The Affordable Housing Plan

The Goal: facilitate the preservation of up to 50% of existing residents in the focus area for a generation, while at the same time transforming 300 vacant properties into affordable housing owner-occupied homes.

How do you hit those numbers in a rapidly appreciating real estate environment? You use a suite of powerful, yet tried-and-true tools, discussed below. But before we get to those tools, a moment to reflect: that number should not be glossed over. If the City of Baltimore were able to rapidly revitalize a dramatically and decadenally disinvested area such as our Key Focus Area and still realize this lofty level of affordable housing preservation and creation, it would represent nothing short of an entirely new model of economic development for the nation - one firmly rooted in the first principles of equity, economic science and righting historic wrongs.

It’s Social Sciences 101 that neighborhoods of wide economic diversity are the most successful at lifting lower income families and children out of poverty. Truly diversifying the income profile of the KFA (not just gentrifying it into a wealthy enclave) could have generational effects on thousands of West Baltimore families and children. The opportunity for poverty eradication through a managed and subsidized (MLK) free market is massive.

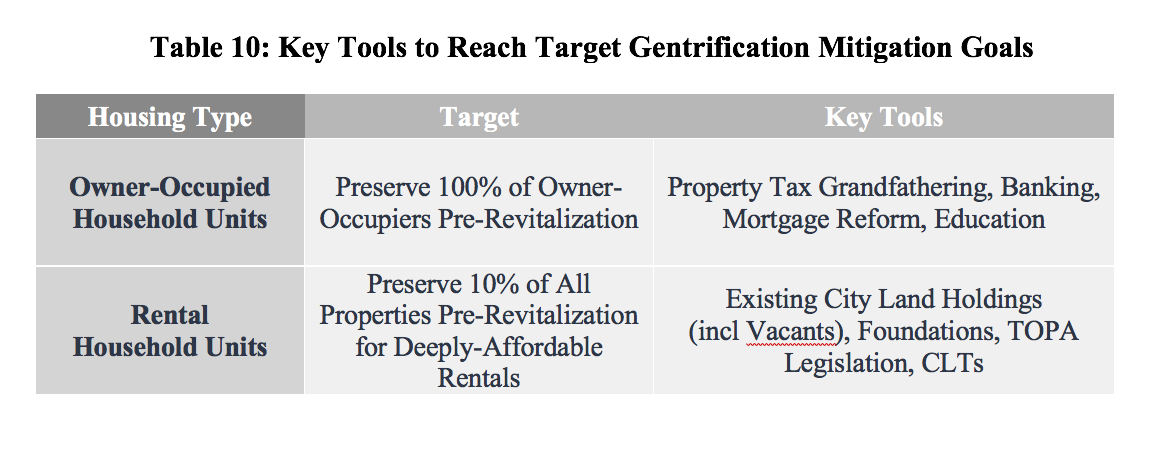

So again, how do we do that? Relentlessly, over time, with a suite of tools:

What would the timing of affordable housing preservation and creation look like?

Key Affordable Housing Tools

1. Property Tax Grandfathering (for existing residents on “Day 1”)

The immediate preservation of 30% of existing residents in the Key Focus Area is no farther away than some simple legislation. Limits on property tax increases are common in many municipalities for certain groups, such as the elderly, disabled or veterans. The home valuation for tax purposes is typically kept at or near a base level, or allowed to increase at some small increment like 1% per year on that base level, often for a number of years, or even decades. Why is that important?

Well, functionally, the only thing that “gentrifies out” existing homeowners is property tax increases in a rising valuation environment. Limits on increases for existing residents on “Day 1” would alter that dynamic entirely, immediately, and cost-effectively, and preserve the ability for 30% of the existing residents - the current owner-occupiers - to remain in their homes in the KFA in perpetuity, regardless of what happens with house prices. Property tax grandfathering is, simply put, a tremendously powerful tool that is underutilized in affordable housing for lack of a powerful constituency - and a tool that is tailor-made for affordable housing preservation in West Baltimore.

2. Vacant Properties (the intelligent disposal of)

The 6000 vacant properties in the Key Focus Area represent perhaps the biggest challenge to economic development, but also the greatest opportunity for creation of affordable housing. This number of cheaply-available properties in such proximity to one of the country’s most powerful economic engines may be unique in America. The most critical aspect of converting Baltimore’s vacants to affordable housing is discussed above - the Cardin Neighborhood Homes Investment Act. Why is it critical? Because it would finally bring the (subsidized) free market to bear on a problem that is so vast, it has never been successfully addressed by the public or foundation sectors.

“It would finally bring the (subsidized) free market to bear on a problem that is so vast, it has never been successfully addressed by the public or foundation sectors.”

But there’s another equally key item that needs to be addressed - the broken Baltimore City tax sale system.

Baltimore City has come under fire recently for favoring community groups over developers in tax sales. But if there’s any hope of keeping property speculators (who have crushed several cycles of economic green shoots in the KFA over the last few decades) at bay, it’s in doing that very thing which may have been the source of the controversy - i.e. not awarding property tax auctions to the highest bidder, but instead working with community groups to intelligently identify what is needed, and how to best ensure renovation of those properties.

The Dollar House program of the 1980s - which required a certain level of investment in a property in a certain amount of time - is one successful model. But there are others as well. The underlying rationale, however, should always be that vacant properties should be evaluated in the same way that larger parcels are - for the best developer, with the greatest chance of completing the development, and the most likely probability of providing real tangible benefits for the community, such as affordable housing.

Again though, it all starts with the city getting control of a tax sale system for vacant and tax-delinquent properties that everyone agrees is not being run in the best interest of city neighborhoods and communities. If all of these vacant properties were to come online as affordable housing, instead of ending laying fallow for years, or worse, as vacant lots gap-toothing formerly seamless blocks - that outcome, together with property tax increase limits for existing homeowners, would mean that it wouldn’t matter anymore how far prices rose in other parcels. An affordable housing, existing resident retention rate of more than 50% would have been achieved. And what’s more - a new national model for economic development will have been established.

To dive more deeply into these tools and others, please see the Affordable Housing section of the website, or Section 7 of the Roadmap Report.